Teaching Composition with Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe is the quintessential dead blonde, and 2022 was a year that reinvigorated public interest in her body and biography. Kim Kardashian shocked film lovers and fashion preservationists alike by wearing to the Met Gala the very flesh-colored sheath dress made unforgettable by Monroe's "Happy Birthday” serenade to our 35th president. And audiences naturally debated the ethics of Blonde, the latest adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ novel and a biopic many viewed as exploitative. It was also the year that I began designing the first iteration of my first-year composition course, “Woman, Image, Myth: The Mediated Afterlives of Marilyn Monroe.”

Marilyn Monroe died on this day sixty-three years ago, on August 4, 1962. She was thirty-six years old. Ever since, she has remained an enigmatic, spectral presence in the public imagination. These days, she haunts my composition classroom.

The Marilyn Question

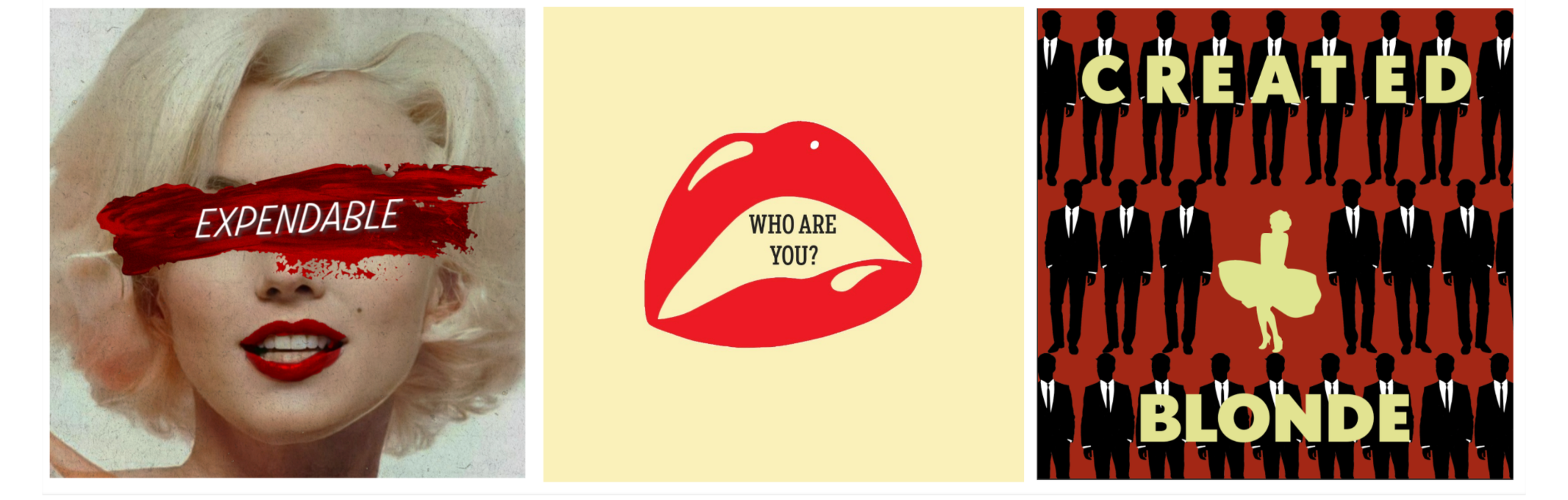

As someone invested in the stories we tell about women artists, Monroe has always struck me for being the woman everyone recognizes but no one knows. That is, we know her face - we recognize her silhouette when we see it plastered on housewares and printed on cheap t-shirts that are bound to peel in the dryer - but most people, especially the college students I have the privilege of teaching, can tell you little more than she was an actor. Or that she was a model. Or that she had an affair with JFK. Don’t bother to ask about her filmography, much less her complicated childhood or passion for literature. Her body is lauded over her body of work, but that’s something I think we can change.

I always begin the semester with this question: What do you know, or think you know, about Marilyn Monroe? There are no wrong answers. “Nothing” is just as acceptable as “she was an Old Hollywood movie star.” Of the 200+ students who have taken this class with me over the years, only a very small handful have had anything more to say. But they’re intrigued by the question. It sparks something in them. They immediately begin to talk about how weird it is to be so intimately familiar with a celebrity’s image but know virtually nothing about her life. They find it strange that they see her face in dentist offices, on a cutout in their neighbor’s garage (true story!), and on the shelves at Hobby Lobby and used bookstores, even though she has been dead for over half a century.

Their first homework assignment? To find and critically assess an object that uses, references, appropriates, or exploits Monroe or her image. Students search eBay, Etsy, Amazon, and Facebook Marketplace, digging up apparel, novelty items, replica memorabilia, cosmetics, and more. My favorite obscure find is none other than a toaster that imprints her face on bread.

Laughter aside, this is the perfect starting point to begin unpacking our shared inquiry question: why always Marilyn Monroe?

Over the next few weeks, we begin exploring, through stories told in essays, images, interviews, and podcasts, the early years that created the conditions for stardom. We survey clips of her performances, unpacking the curse of typecasting and Monroe’s true range, and prepare to create multimodal film reviews of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. In this first major project, we put the artist — Marilyn at her best as Lorelei Lee — first. With a shared understanding of the depth of Monroe’s talent in place, we can then begin to unpack how and why the circumstances surrounding her death have overshadowed her life.

Centering Conspiratorial Rhetoric

Americans seem addicted to true crime. It’s an impulse I’ve never quite understood, but it’s not a surprising one. I’ve read enough Hollywood Babylon wannabes over the years to know that we, as a culture, are both attracted to and repulsed by the exaggerated, grotesque downfalls of famous people we’ll never meet.

Monroe’s death, a likely accidental barbiturate overdose, was quickly made into something suspicious. A politically-motivated assassination made more sense, surely? After all, we seem to have a difficult time accepting beautiful women who die young.

The unit that follows our study of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is not about proving what happened to Monroe or arguing that a particular conspiracy has merit. Instead, we use texts ranging from obituaries and biographies to Buzzfeed videos and FBI files as case studies to unpack the rhetoric of conspiracy theories.

What are the stories we tell about Monroe’s death? Who all do we try to implicate, and why does placing blame on the Kennedys, or the mafia, or the CIA, or the Hollywood machine, or aliens make us feel better (or worse) about a beautiful woman’s untimely death? Who wields the power in shaping these narratives? How are biographies - books we take at face value - inherently biased? What genres perpetuate these myths? And what are the implications for Monroe’s legacy and our cultural memory?

These questions that guide our discussions and students’ projects are eye-opening and quickly make clear the necessity of critical thinking and careful rhetorical analysis. Out of all the texts I’ve assigned over my many years teaching college writing, few others have prompted students to recognize and discuss, on their own terms, the importance of audience and genre awareness with the level of detail and precision that I see here.

And it’s especially encouraging to see how students take these questions or lenses and interrogate their own related interests in the subsequent unit. We start with Monroe as our shared inquiry topic and work outward, each student spinning off to investigate a topic of interest within the universe of our course: conspiracy theories, women in media, American politics and culture at mid-century, celebrity deaths & true crime cases, etc. I learn a great deal from my students’ projects, especially those that apply their newly developed rhetorical analysis skills to current celebrity controversies. They keep me inspired to continue studying how we treat women artists and their legacies, even when my professional obligations lead me elsewhere.

So, on this anniversary of Monroe’s death, I ask you to slow down the next time you see her face. It’s the least we can do.

Want to learn more about my course design? Click through my course spotlight to explore assignments, course readings, and student evaluations.

As always, thanks for reading. If you have questions about any of my content or have ideas for collaboration, please contact me at gabrielle@gabriellestecher.com.